LDD 04 | Maggio 2016

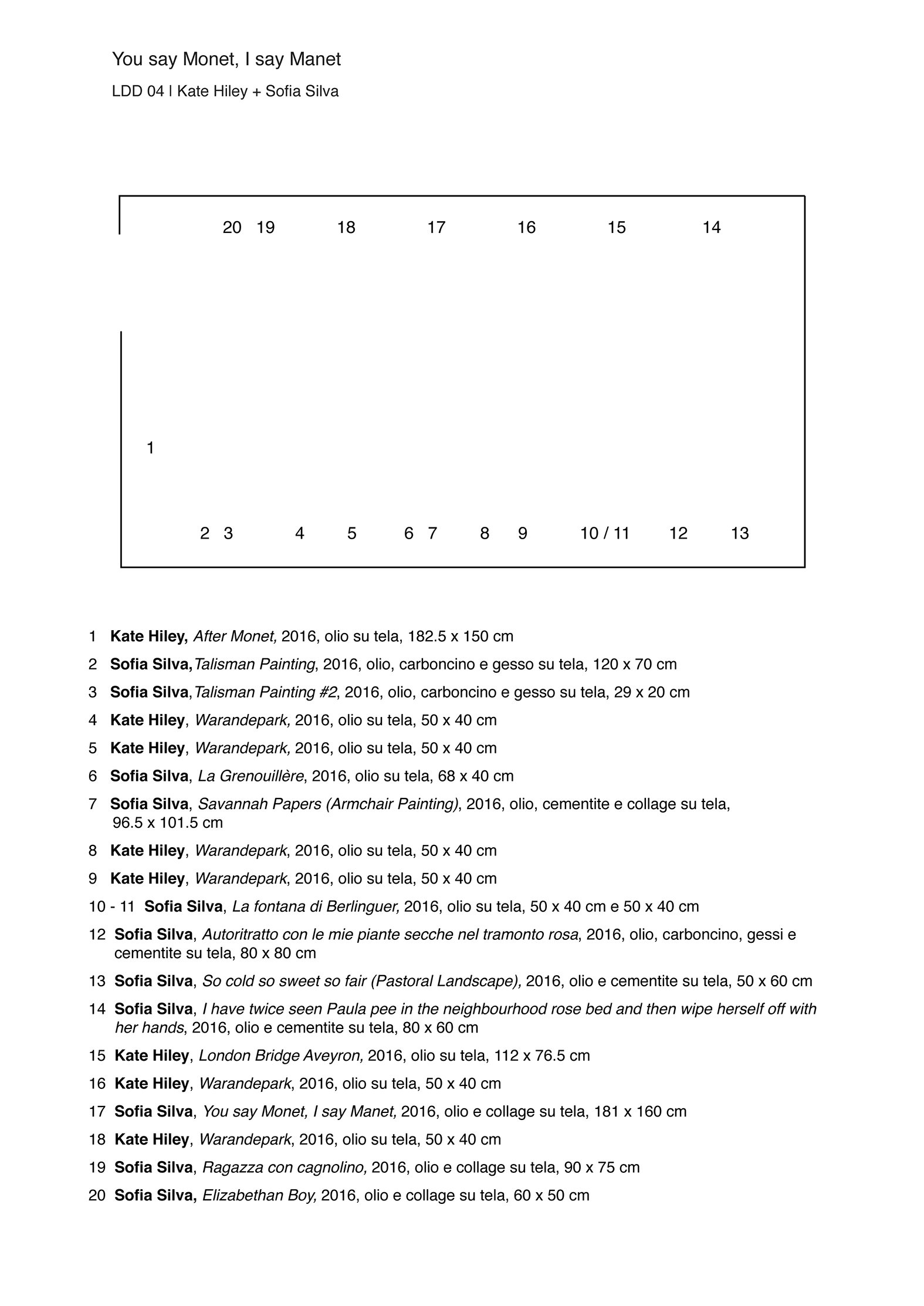

Kate Hiley + Sofia Silva

You say Monet, I say Manet.

19 maggio 2016 – finissage

* DUPARC CONTEMPORARY SUITES, Corso Massimo d’Azeglio, 21, 10126 Torino.

Ore 8.30 Kate si è appena svegliata, preferisce cucinare la prima colazione nel nostro appartamento. Si lava il viso e prepara un piatto di porridge, miele e semi. Usa un piatto fondo, non una scodella. Io siedo a un tavolo del piano ristorante. Ho fatto colazione con due fette di pane e marmellata di fragole, mezza girella all’uvetta, un’albicocca sciroppata, un bicchiere di succo di mela, una tazza di tè verde al gelsomino.

Ore 14.30 Ho infornato una fetta di torta salata. Penso che mangerò quella e poi mi farò un piatto di pomodori cuore di bue con sale e olio. Kate ha lavato i piatti del giorno prima, mi chiede se posso asciugarli. Le dico che non c’è problema. Kate mangerà asparagi, broccoli al vapore, un piatto di pasta, pomodorini lessi con le lenticchie e finocchio a cubetti.

Ore 14.03 Kate mastica a collo alto, tranne che per alcuni secondi in cui appoggia la testa sul palmo di una mano.

Ore 21.30 Mangio straccetti di manzo e una patata. Poi uno yogurt Müller bianco con fiocchi di cioccolato e una decina di ciliege, le prime della stagione. Kate mangia tre bignole, una porzione di farinata e una pizza marinara.

Il nostro salotto è ampio otto metri per cinque, ha la moquette grigia, i divani sono rivestiti di velluto rosso. Sul muro a sud è appeso un quadro di Schifano: un vecchio rosa elettrico tiene le mani conserte mentre riposa tra un fogliame di lacche.

13 maggio 2016 – reading

‘Tu dici Nabokov, Я говорю Набоков (I say Nabokov)’

Lettura trilingue de ‘L’occhio’ di Vladimir Nabokov.

Introduzione di Gianluigi Ricuperati. Letture di Sofia Silva (italiano), Kate Hiley (inglese) e Lidiya Liberman (russo).

9 maggio 2016 – opening

Sofia Silva: Ci siamo incontrate in uno strano luogo dove ai pittori era chiesto di scrivere e di parlare, molto spesso controvoglia. Non ho mai creduto al mito del pittore silenzioso, ma comprendo come la mente di un pittore possa abituarsi a un pensiero privo di parole. You say Monet, I say Manet sottolinea come la pittura sfoci in una questione linguistica. Spesso si crede che le immagini costituiscano un linguaggio universale, ma sono convinta che la pittura non lo sia. La pittura e il modo in cui la percepiamo cambiano da lingua a lingua, da paese a paese, da città a città; guardare un dipinto è anche liberarsi dal proprio inconscio visivo per abbracciare quello di un’altra persona, è un esercizio di libertà. Molto spesso il pittore conquista questa libertà dimenticando. Painting is the greatest form of freedom, ma le immagini non lo sono.

Kate Hiley: Sì, la pittura è un delicato gioco da equilibristi. Essere pittore significa costruire un linguaggio e riuscire a farsi leggere, e ciò avviene solo ponendo un contrappeso. Lo stesso equilibrio è da trovarsi nella percezione che il pittore ha di sé. E sì, in quello strano equilibrio bisogna dimenticare tantissimo, se è questa la libertà di cui parli. Penso alla concentrazione del funambolo che cammina sulla corda, libero da pensieri. Spesso mi chiedo se i grandi dipinti siano frutto di un totale stato di libertà o se piuttosto non nascano quando si cammina sul filo del rasoio, a metà tra libertà e controllo.

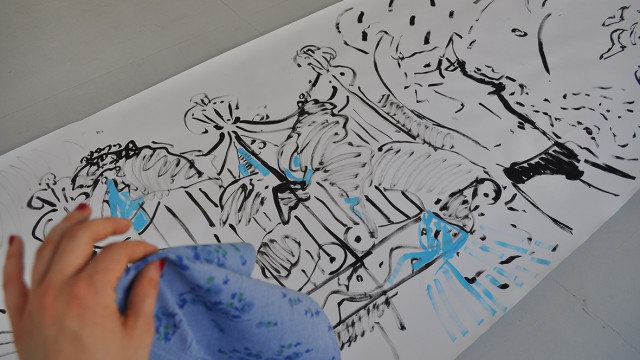

Sofia: La libertà totale è troppo pazza e dopo un po’ annoia; penso che il pittore dia il proprio meglio mentre lotta per conquistarla, non quando l’ha in pugno. Mi piace dipingere me stessa. Sono una musa facile e mi diverto ad allungare e accorciare le linee del mio viso. Sono sempre stata attratta dal modo in cui i pittori a un certo punto della propria vita cristallizzano il loro modo di disegnare la figura umana. I dipinti che espongo a You say Monet, I say Manet mi sembrano molto gioiosi e a volte percepisco questa gioia come una pena, come se un’ombra scura scendesse sull’allegria facendola sembrare un sentimento meno degno di altri. Mi piace pensare che la ragazza che fa capolino nei miei dipinti sia un’allegoria della pittura, una giovane che fa esperienza della vita per la prima volta, senza un’idea ben precisa.

Kate: Sì, anche io vedo questo nel tuo lavoro. La tua non è una felicità zuccherosa, ma una gioia satura che non si trova nella pittura recente, specie in quella non astratta e nel ritratto. I ritratti gioiosi dell’ultimo secolo spesso portano con sé un sottotesto macabro o marcati riferimenti sessuali. Forse è perché non abbiamo vissuto alcuna guerra di portata pari a quella dei due conflitti mondiali, ma oggi vi è come la sensazione che sia troppo facile dipingere la gioia, perché viviamo in un tempo privilegiato. Se guardi a Monet, ai suoi ultimi lavori dipinti dopo la guerra, è limpido come egli cercasse la beatitudine dopo il dolore estremo e quel linguaggio ancora risuona nelle opere. Poiché nei miei dipinti lavoro con il paesaggio (forse lontana dalla paura di aggiungervi figure o oggetti), mi viene spontaneo pensare alla gioia con cui e in cui lavorava Monet. Mi è naturale cercare la luce e il movimento nella natura più che nella figura umana. Per questo rimango sempre catturata dalla tua capacità di fare ritratti e autoritratti con così tanta lievità.

Sofia: Grazie, cosa intendi per lievità?

Kate: La lievità delle tue figure non le priva delle emozioni, al contrario di ciò che accade per le figure scultoree sulle tele di Lüpertz, che pure amo. I tuoi personaggi hanno un carattere e un sentimento, una loro posizione. Penso che la lievità stia in questo: nei tuoi lavori separi il soggetto – o te stessa, nel caso dell’autoritratto – da tutti i riferimenti pittorici, sfondo, oggetti, rimandi, che li accompagnano. In questo modo le tue figure umane assumono anche il ruolo di chi osserva, acquistano una posizione d’introversione nel tuo mondo estroverso, un po’ come Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie.

Sofia: Tu hai costruito un mondo privo di persone. Non è primitivo, né selvaggio, quanto piuttosto malinconico, dolce e abbandonato. Guardando i tuoi dipinti, vedo parchi di ville deserte che mi ricordano i giardini romani di Velázquez. Cerchi con costanza di mantenere una pennellata veloce e mascolina, ma ne emergono campi ricchi di memoria, d’amori passati, vacanze e tempeste. I pittori che ho cercato di più nella mia vita sono quelli che hanno ritratto guerra e angoscia, libertà e amore nelle feste campestri, nei picnic, nei giardini, in paradiso: Watteau, Tiepolo… Penso che la ragazza che abita i miei dipinti si divertirebbe moltissimo nei tuoi campi.

Kate: M’incuriosisce che tu possa trovar traccia di ricordi e storie nei miei paesaggi. È un gran complimento poiché è qualcosa che si fa strada senza che io me ne accorga. Quando dipingo, i paesaggi vengono da sé, senza pensarci troppo; s’innalzano come scenografie teatrali o sfondi pronti ad accogliere figure che poi non sopraggiungono. Come hai detto, sono stati abbandonati. Tuttavia spero sempre che in questi miei paesaggi si possa ancora avvertire la figurazione, la presenza umana. Non sono una grande amante di Watteau, della sua pittura e della sua tavolozza, ma è vero che l’indulgenza che spande nei suoi quadri può diventare una droga. Penso che il suo linguaggio abbia a che fare con l’idea di paradiso. Un paradiso della mente? Uno reale? Visivo? Un paradiso dove si faccia a meno delle parole? Lo stiamo veramente cercando? Paradiso è una parola cui torno spesso. Dopo l’angoscia di tutti quei pittori che hanno cercato di raggiungere il sublime ascoltando la propria sofferenza, in che modo possiamo arrivarci noi? È già nato il paradiso che sto cercando? L’ha già dipinto qualcuno? Non sono così sicura.

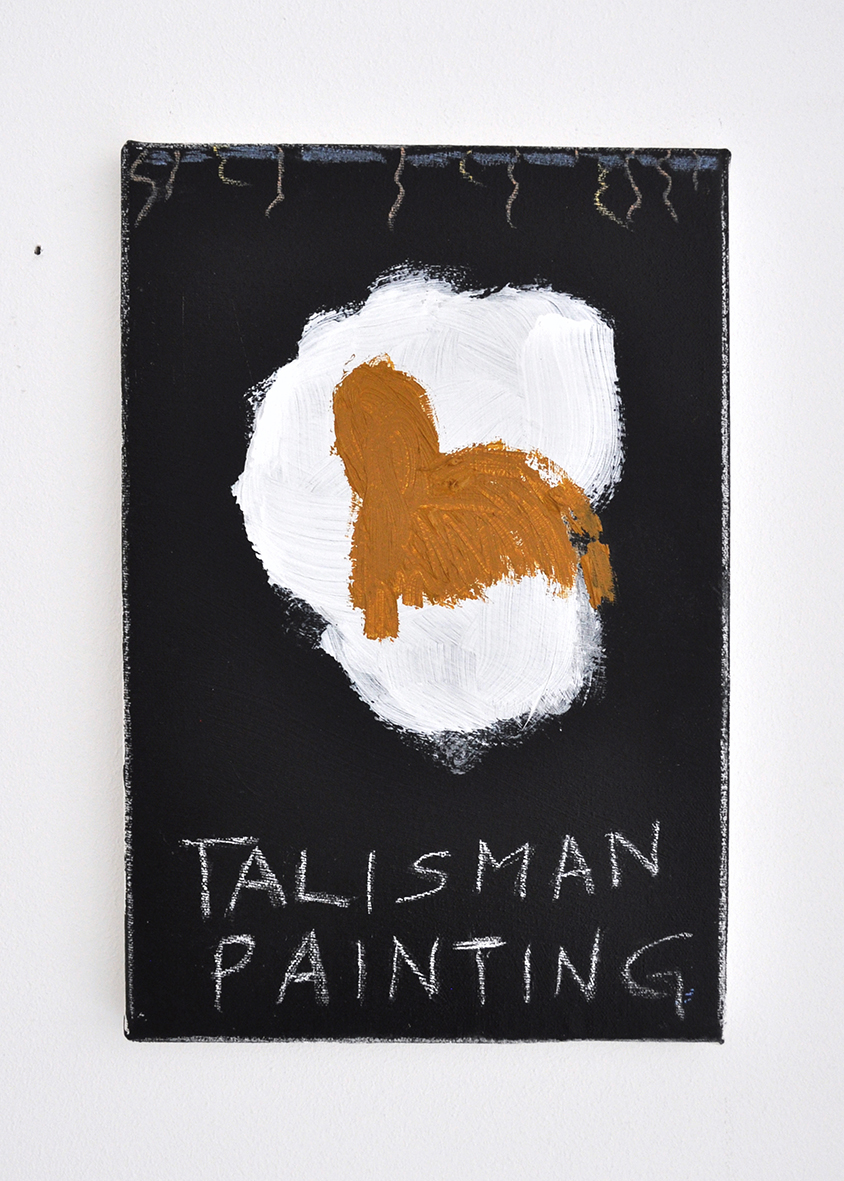

Sofia: Due anni fa titolai una mia mostra Eden Amiss; quel titolo mi sembra assumere una certa rilevanza in questa conversazione. Penso che giardini e paradisi siano sempre stati molto importanti per i pittori: i confini e i recinti di un giardino richiamano le estremità del telaio. Tutto sta nel prendersi cura del limite o nel decidere di infrangerlo, da Pompei, al gotico fiorito, da Monet ai maestri del contemporaneo. Sì, penso che l’idea di paradiso lavori nella tua mente come metafora della composizione. Un luogo dove tutto è disposto secondo un ordine e tu puoi decidere se mantenerlo o no. Mentre dipingo penso sempre a come infrangere l’ordine compositivo in maniera inedita. Quel che prediligo in un pittore è il coraggio; io stessa meno capisco la composizione di un mio dipinto, più ne sono felice. Mi dà un brivido. Sono proprio ossessionata dalla composizione, temo sempre che il mio occhio possa adagiarsi inconsciamente su immagini o strategie compositive. Un nostro caro amico, Poblete-Bustamante, dice che painting deve essere un errore. Qualcosa di sbagliato che succede per caso, in grado di aprire nuove porte al medium e all’occhio. A volte questo errore non è bello e nel trovarselo davanti le persone si spaventano o semplicemente lo trovano inguardabile. Aggiungerei che questo errore deve avere una sua armonia, e per trovarla non deve dimenticare il passato.

Kate: Sì, è proprio la questione del limite, i bordi della tela, i muri di un giardino… O semplicemente il limite stesso della pittura, materia su una superficie. I limiti ci permettono di creare, di esperire il sublime, di compiere questi errori necessari. Senza regole e ordine l’errore nemmeno esiste. E quindi anche in pittura occorrono limiti per cercare la libertà. La conoscenza della storia dell’arte può costituire un ostacolo; cerco di lasciar da parte la conoscenza per poi riportarla nell’opera, secondo un principio nuovo e bello.

Sofia: Quel che è sbagliato non esiste in pittura. Correzione, rimedio, soluzione, aggiustamento, distruzione: nulla di tutto questo è sbagliato. Sregolatezza, sbaglio e libertà sono idee che a volte vengono ingiustamente sovrapposte, quando sono invece così lontane tra loro.

Kate: Essendo la pittura linguaggio non la si può definire sbagliata poiché l’errore è in realtà un neologismo. Mi diverte molto quando ci affidiamo al linguaggio delle parole per descrivere la pittura che di per sé è un linguaggio parallelo a quello scritto o parlato.

Sofia: Penso che entrambe abbiamo in qualche modo dimenticato le avanguardie ed è da questo piccolo traguardo che mi piacerebbe proseguire con la mia opera. Voglio scavalcare l’avanguardia e il postmoderno per inventare sentimenti e forme nuove. Certo che nella vita noi siamo tutto tranne che dimenticone, è un più un desiderio quello di dimenticare che una conquista. Come artista però so per certo che non mi voglio occupare né guardare al XX secolo. Penso che tutto questo si possa rintracciare in Autoritratto con le mie piante secche nel tramonto rosa, una veduta della mia mente alle sei di pomeriggio; vedo fontane, ortensie, pezzi di marmo e una certa sensazione che proviene dal libro che tengo in mano.

Kate: Anche a me piacerebbe scordare il XX secolo, e penso che ci stiamo riuscendo. L’unico aspetto che mi porto dietro dalla pittura del Novecento è una certa strutturazione tecnica. Trovo molto più interessante guardare da Monet in giù. Non è un linguaggio rintracciabile nel contemporaneo, ma nemmeno m’interessa che lo sia; per me You say Monet, I say Manet celebra anche questo.

*

Kate Hiley (1988) e Sofia Silva (1990) s’incontrano a Londra nel 2012 negli studi di Turps Banana, covo d’artisti che ruotano intorno all’omonimo magazine. Turps è una rivista scritta, curata e pubblicata da artisti che in tredici anni hanno raccolto le dichiarazioni e le confidenze più preziose dei grandi pittori del nostro tempo. L’amicizia continua ed entrambe hanno affiancato alla pittura altre attività: Hiley è una curatrice attiva nel Regno Unito e in Francia e ha co-fondato a Parigi Le Cabinet Dentaire; Silva insegna a Turps in qualità di mentor e scrive d’arte per giornali e riviste. Hiley e Silva hanno collaborato altre volte prima di You say Monet, I say Manet; le più recenti esposizioni che hanno visto i lavori di entrambe le artiste sono Figure This Out (Assembly House, Leeds), Stripped to Tease (LOCOMOT, Vienna) e Vis-à-vis (Le Cabinet Dentaire, Parigi).

——-

english versione below

LDD 04 | May 2016

Kate Hiley + Sofia Silva

You say Monet, I say Manet.

19th May 2016 – finissage

*DUPARC CONTEMPORARY SUITES, Corso Massimo d’Azeglio, 21, 10126 Torino.

8.30 am Kate just woke up, she prefers having breakfast in our apartment’s kitchen. She washes her face and cooks some porridge with honey and seeds. She eats in a soup plate, not in a bowl. I sit at the restaurant table. I’ve had my breakfast: two slices of bread with strawberry jam, half of a raisin croissant, an apricot in syrup, a glass of apple juice, a cup of green jasmine tea.

2.30 pm I’ve baked a slice of quiche. I think I’ll have that with a dish of oxheart tomatoes with oil and salt. Kate has washed the dishes from the day before, she asks if I can dry them off. I tell her yes I can, no prob. Kate will have asparagus, steamed broccoli, some pasta, baked little tomatoes with lentils and cubes of fennel.

2.03 pm Kate chews keeping her neck very straight, with the exception of a few seconds when she rests her face on the palm of her hand.

9.30 pm I’m having beef Stroganoff and a potato. Then a Müller yogurt with chocolate flakes and then ten cherries, the first of the season. Kate eats three bignola pastries, a portion of farinata and a pizza marinara.

Our living room is eight by five metres, has grey moquette, the sofas are covered with red velvet. A painting by Schifano is hung on the southern wall: an electric pink old man with his hands folded rests in between a lacquer foliage.

13rd May 2016 – reading

‘Tu dici Nabokov, Я говорю Набоков (I say Nabokov)’

Three- languages reading of ‘The eye’ by Vladimir Nabokov.

Introduction by Gianluigi Ricuperati. Readings by Sofia Silva (italian), Kate Hiley (english) and Lidiya Lieberman (russian).

9th May 2016 – opening

Sofia: We first met in a very strange place, a place where painters had to speak and write, sometimes even against their wish. That first studio we shared was an empire of words. I don’t believe in the myth of the silent painter but I realise how the painter’s mind can get accustomed to a wordless thinking. You say Monet, I say Manet underlines how painting can become a linguistic issue. It’s often believed that images constitute a universal language, but I truly think that painting is not universal. Painting and our perception of it changes, from language to language, from country to country, from town to town; to look at painting is an exercise of freedom from one’s unique visual origin and background. For a painter that freedom is found in the process of keeping and forgetting, valuing and also not really valuing one’s work. Painting is the greatest form of freedom whereas images are not.

Kate: Yes painting is that delicate game of balance. To be a painter is to develop your language and then to convey it, and only through the process of balancing is that an achievable goal. We must also strike a balance in the way we view ourselves as painters, both through the eyes of those observing us and through our own self inflicted view. And yes, within that state of equilibrium we must works hard to forget, that is the freedom you’re speaking of. Much like the focus one must find when walking a tightrope and all irrelevant thoughts are put out of the mind. The question I often ask is, are great paintings made from a complete state of freedom, or are great paintings made when walking that tightrope between personal and external?

Sofia: I would say: “Beware of total freedom”; the best form of freedom in painting comes when the painter is struggling to achieve it, not in the accomplishment of it. I like painting myself. I am an easy muse; I always find myself joking when painting my face. I’m attracted to how painters shape their own immutable way of drawing the human body. These paintings that I’m showing in You say Monet, I say Manet feel joyful; sometimes I read this as a stigma, as if there was a dark shadow cast over joy, mirth and cheerfulness as emotions, taking away their dignity. But never the less, they are full of glee. The girl that constantly emerges from my paintings is an allegory of painting itself as a joyful young woman, who experiences life for the first time with no set ideas.

Kate: Yes I see that in your work, it’s not a sugar coated glee but a kind of saturated joy that you don’t see so much in non abstract painting anymore, especially when it comes to portraiture. Any joyful portrait from the last century would have to come with a macabre subtext or some kind of sexual reference. Perhaps because we haven’t lived through a direct personal attack in the west of the same immense scale since World War One or Two, it seems too easy to be celebratory or happy, because we live in a privileged world for the time being.

If you look at Monet and his later works made after the war, he was searching for some kind of bliss in a time of extreme pain and that language resonates in the work even now. Because I work with landscapes in my own paintings (perhaps out of a temporary fear of adding the figure or object) I can obviously connect with that joy in Monet’s work much more directly. It feels natural to me to search for life and light in nature much more so that in humans. This is why I’m interested in your ability to make a portrait, and a self portrait, with such a lightness.

Sofia: Thank you, although what do you mean by lightness?

Kate: The lightness in your figures does not make them emotionless like for example, Lüpertz’s sculptural figures, which I enjoy very much also. Your figures have a character and a feeling, that is their position. I think the lightness is that, within your works, you can separate your figure or your “self” from the references swirling around them on the picture plane. In this way the figure in your paintings becomes the observer, it becomes the introvert placed in your extrovert world, like Alice in wonderland. That’s the world you have created in your work for the viewer to inhabit…

Sofia: And in your paintings you have constructed a world that is empty of humanity. It doesn’t feel primitive nor wild but it has a melancholic and sweet state of abandon. To me yours are parks of deserted villas a bit like Velázquez’s Roman gardens. You constantly try to achieve a fast and masculine mark but what comes out from your paintings are parks full of memory of past loves, holidays and storms.

I’ve always been attracted by those painters who have portrayed war and anguish, freedom and love in parties, picnics and heavens. Watteau and Tiepolo for example. I think that my girl would enjoy your parks a lot.

Kate: That’s quite interesting, the fact that you can feel memories and stories in my landscapes. It’s a great compliment because it must be something that seeps it’s way into them without my noticing. In my eyes I create them quite automatically in the moment. They are like theatre sets or backdrops for something figurative. Like you said, it’s as if they have been deserted. Even if this is how they are made, I hope that the figuration in them is present in the absence of the figure – that you can still feel the human presence within them. I’m not the greatest fan of Watteau’s language in his painting or palette, his technical elements, but it’s true that the indulgence of his works are almost addictive. Do you think all of this language feeds into the idea of a paradise? A paradise of the mind or a physical paradise or even a visual one, where the language of words is not needed. Are we even looking for a paradise? That’s a word that I keep coming back to. After anguish people look for the sublime, for the calm, so how do we search for that now when we have little anguish to feed from? It has become too self indulgent perhaps; the anguish versus the sublime, the paradise, how do we explore that language with authenticity now… Can that paradise be found in visual history and references? I’m not so sure.

Sofia: I did a show two years ago that was called Eden Amiss and that title and exhibition now feels very relevant to this conversation. I think that gardens and paradises have always been a matter of great importance to all different kinds of painters because the borders and walls of the garden recall the edges of the canvas. It’s all about taking care of the limit or deciding to break the limit, from Pompei to the late Flamboyant style, to Monet and the contemporary masters. Yes, I think that the paradise works in your mind as a metaphor of your compositional thinking. A place where everything has it’s own place and where you can choose to keep or break this order.

Within my painting I always think about how to break the order in an original way. I value braveness in painting and the more I don’t understand my paintings the more I am happy with them. It gives me a thrill. I am obsessed by composition and afraid of the idea that my eye might be or become accustomed to strategies that I don’t wish to foster. A great friend of ours, Poblete-Bustamante, always says that painting is and must be a mistake. Something wrong that happens by chance, something that then opens new doors to the medium and to the eye. Sometimes the mistake doesn’t look good, sometimes people find it scary or at other times unwatchable. I would add that it has to be a harmonic mistake, even if that sounds like an oxymoron, it must be a mistake that doesn’t forget the past.

Kate: It’s the thing of limits isn’t it; the edge of the canvas, the wall of the garden… or simply the limit of painting itself, material on surface. The limits allow us to create and find the sublime and to make those necessary mistakes. Without rules and order, a mistake cannot exist. We need the limits to find freedom which as you said is an oxymoron. Our knowledge of history of art, when we know so much of these references, it can become so difficult to break away from them even consciously – to “break the order”. We have to break away from the past in order to have the freedom to bring it into the work in a beautiful way.

Sofia: It’s very true that the concept of wrongness doesn’t exist in painting. Correction, remedy, solution, fixing, destruction: nothing of this is wrong. Sometimes we just superimpose wildness, wrongness and freedom but all these things are very different from each other.

Kate: Exactly! Nothing is ever “wrong”. As in painting as in life, anything we would define as wrong with our language is simply a different route to the same outcome, a way to learn, develop and create. The word wrong is in itself misleading because it suggests something negative, as does the word mistake. It’s ironic that we rely on the language of words to describe painting, something that in itself exists as a language for the things we are not able to convey with the written or spoken word.

Sofia: I think that both of us have in some ways already forgotten the avant-garde, and it’s from this point that I’d like to move forward with my work. I’d like to overstep the avant-garde and the postmodern, to find and pursue original emotions and forms. It’s funny because in real life we are all but forgetful you and I, forgetting is a desire for us more than an achieved conquest. As an artist I don’t want to indulge on the XX century. I think these things can be seen in Self-portrait with my desiccated plants in the pink sunset. It’s a view into my mind at 6 pm and I can just see fountains, hydrangeas, marbles and there’s a certain feeling from the book I’m reading.

Kate: I’d like to move beyond the XX century also, in fact in some ways I suppose we both have – what is it that we have taken from it? For my part it is the technical structure. I’m more interested in referencing from the works of Monet and earlier. It’s not a language that is necessarily embraced in our contemporaries, but neither is it something I am afraid of anymore, for me this exhibition is a celebration of exactly that.

*

Kate Hiley (1988) and Sofia Silva (1990) met in London in 2012 whilst both painting on the Turps Banana programme. Turps is a magazine written, edited and published by painters alone. In its thirteen years of activity it has collected some of the most intriguing declarations and confidences from the great painters of our time. Hiley and Silva joined that community of writing-painters and shared the studio for a year. Since that experience, both of them have developed new activities alongside their painting practice: Hiley became a curator in the UK and France, co-founding Le Cabinet Dentaire in Paris; Silva took on the role of ‘mentor’ at Turps and started writing about art for magazines and newspapers. You say Monet, I say Manet is not the first collaboration for Hiley and Silva; recent shows where both of them have exhibited include Figure This Out (Assembly House, Leeds), Stripped to Tease (LOCOMOT, Wien) and Vis-à-vis (Le Cabinet Dentaire, Paris).

*

(ph. Kate Hiley, Sofia Silva)